Name, Image, Likeness — But Make It Gen AI

The legal reckoning to come

Copyright infringement and lawsuits are nothing new. However, the latest significant Supreme Court ruling on the subject begs the question of what kind of legal reckoning is impending as it relates to generative AI. The case: Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith. The controversy? Justices’ influence in evaluating artistic expression.

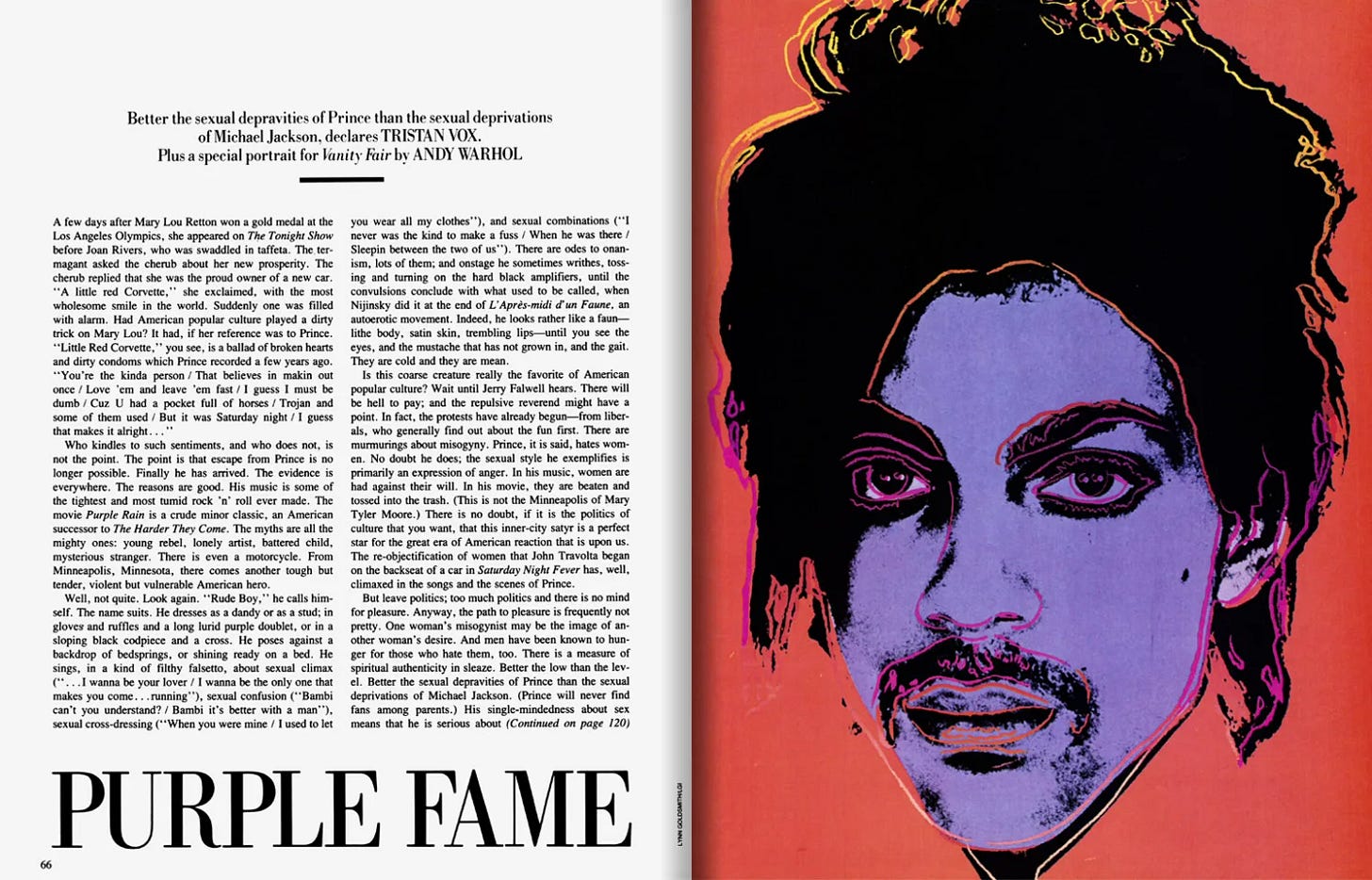

The context: Lynn Goldsmith is known for photographing a variety of famous individuals, including Prince. In 1984, Vanity Fair asked to use one of her Prince photos as inspiration for an Andy Warhol painting to be displayed on their magazine cover. Goldsmith agreed and was paid $400.

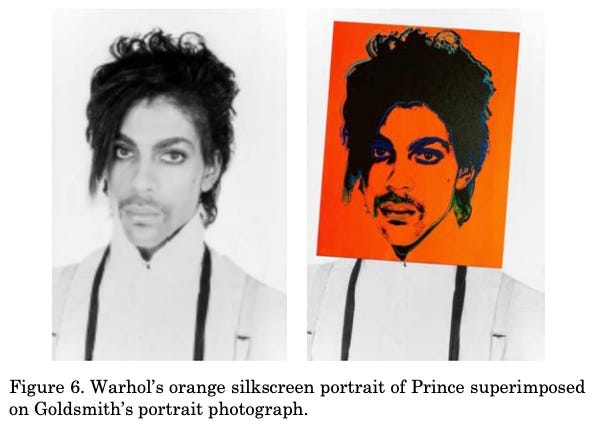

When Prince passed away in 2016, Vanity Fair commemorated his life with one of Warhol’s paintings, a slight variation on the original, called “Orange Prince.” The Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF) was paid $10,000. Goldsmith felt that AWF and Vanity Fair should have credited and paid her too, as “Orange Prince” remains a derivative of her work.

The Ruling: In a 7-2 decision, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Goldsmith. In summary, SCOTUS stated that the debate shouldn’t be about whether “new expression, meaning, or message” makes a “new” piece subject to copyright law. Among other factors, the court held that Warhol's "original photograph and AWF’s copying use of it share substantially the same purpose" of depicting Prince for commercial use in a magazine.1

However, making things more complicated, Kagan (joined by Roberts) wrote a dissenting opinion, expressing concern that:

“…overly stringent copyright regime actually stifles creativity by preventing artists from building on the work of others.”

In the case of Warhol specifically, Kagan writes,

“[Warhol] started with an old photo, but he created a new new thing.”

The core of this case ties back to the intent of copyright law:

“To promote the progress of science and useful arts,” and “induce and reward authors…to create new works and to make those works available to the public to enjoy.”

The intent of the law is somewhat tautological in the case of art, if artists “build on the work of their predecessors.” What is new, Goldsmith’s photo or anything following (including Warhol)? Is anything artistic truly new?

Arguably, the debate remains open and subject to interpretation in future cases of copyright, licensing, and creating derivatives of NIL. The issue becomes particularly tricky in the case of AI, which is predicated on synthesizing existing information and work.

Applicability in Gen AI

The obvious controversy within gen AI is how a model is trained. For example, the current class action motion against Microsoft, GitHub, and OpenAI make some companies fear what training set is allowable. In response to this legal risk, some platforms are taking a “safer” bet; for instance, Adobe is training Firefly solely on Adobe Stock images, openly licensed content, and public domain content (where copyright has expired).

I think the more interesting question that is analogous to, but not the same as copyright pertains to NIL. While AWF v. Goldsmith was labeled a copyright case, much of what was debated actually pertains to NIL: Goldsmith felt that her photography style’s likeness was apparent in Warhol’s depiction of Prince.

Name, Image, Likeness (NIL)

NIL is a legal term that comes from a court case on whether the NCAA could limit education-related payments to student athletes (NCAA v. Alston). Because the term is so apt, I’d like to apply it here to what I anticipate will be a major legal question in generative AI.

If you’ve played around in gen AI tools, you’ve probably experimented with output in the likeness of a particular person, entity, etc. Some examples I’ve seen:

Text: Write a conversation about the 2020 presidential election between Kramer and Costanza as if in Seinfeld

Music: Create a song collaboration between Drake and The Weeknd

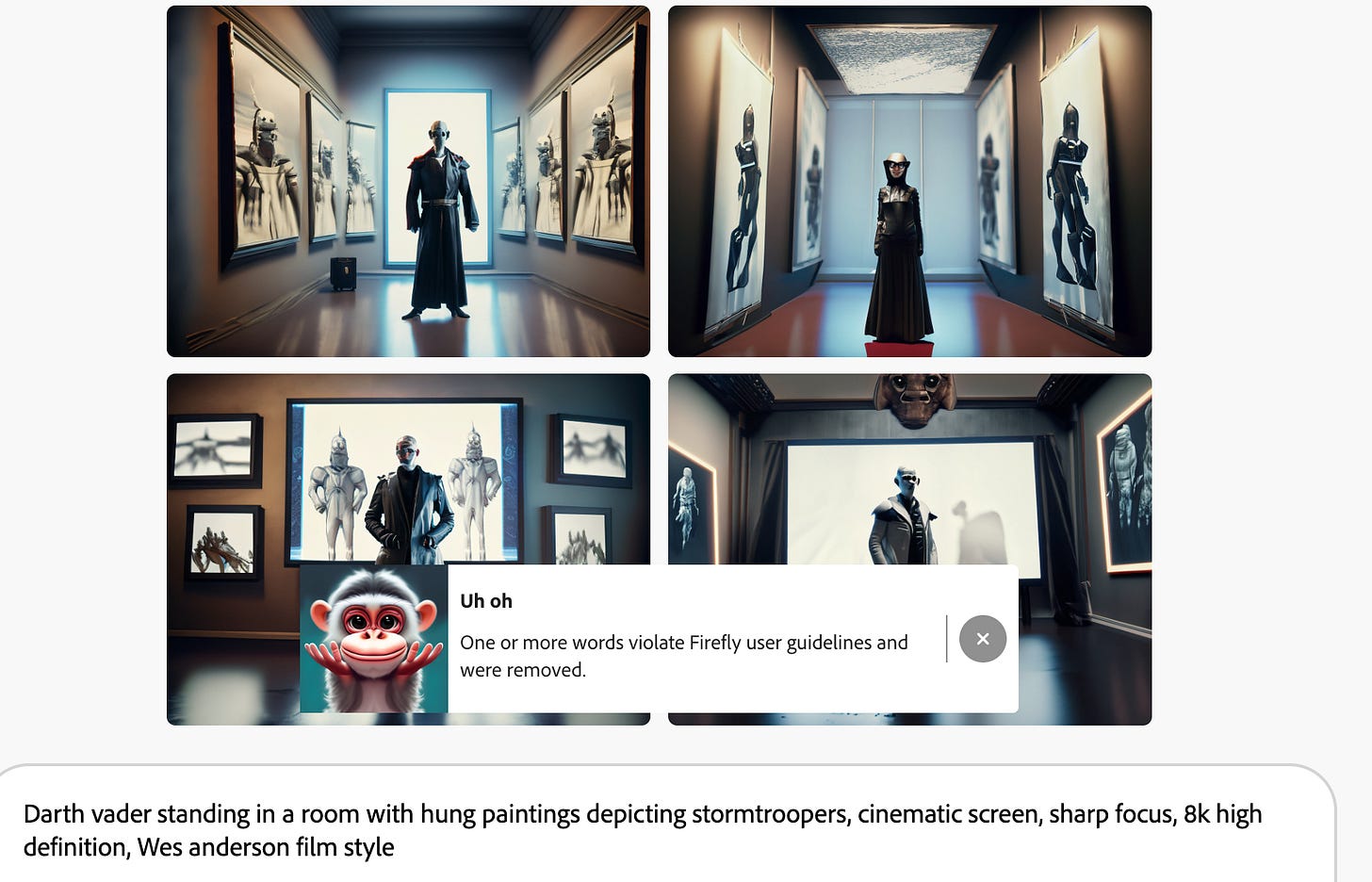

Image: Darth Vader standing in a room with stormtroopers, in Wes Anderson film style (a nod to my previous post)

Video: A girl and fantasy animal exploring in the forest, in the style of Chihiro in Ghibli’s “Spirited Away” and Totoro in Ghibli’s “My Neighbor Totoro”

Where do you draw a line? In my image example, Midjourney (the platform I used) or I could get in trouble with two different entities: Wes Anderson and Disney (which owns Star Wars).

The Reckoning

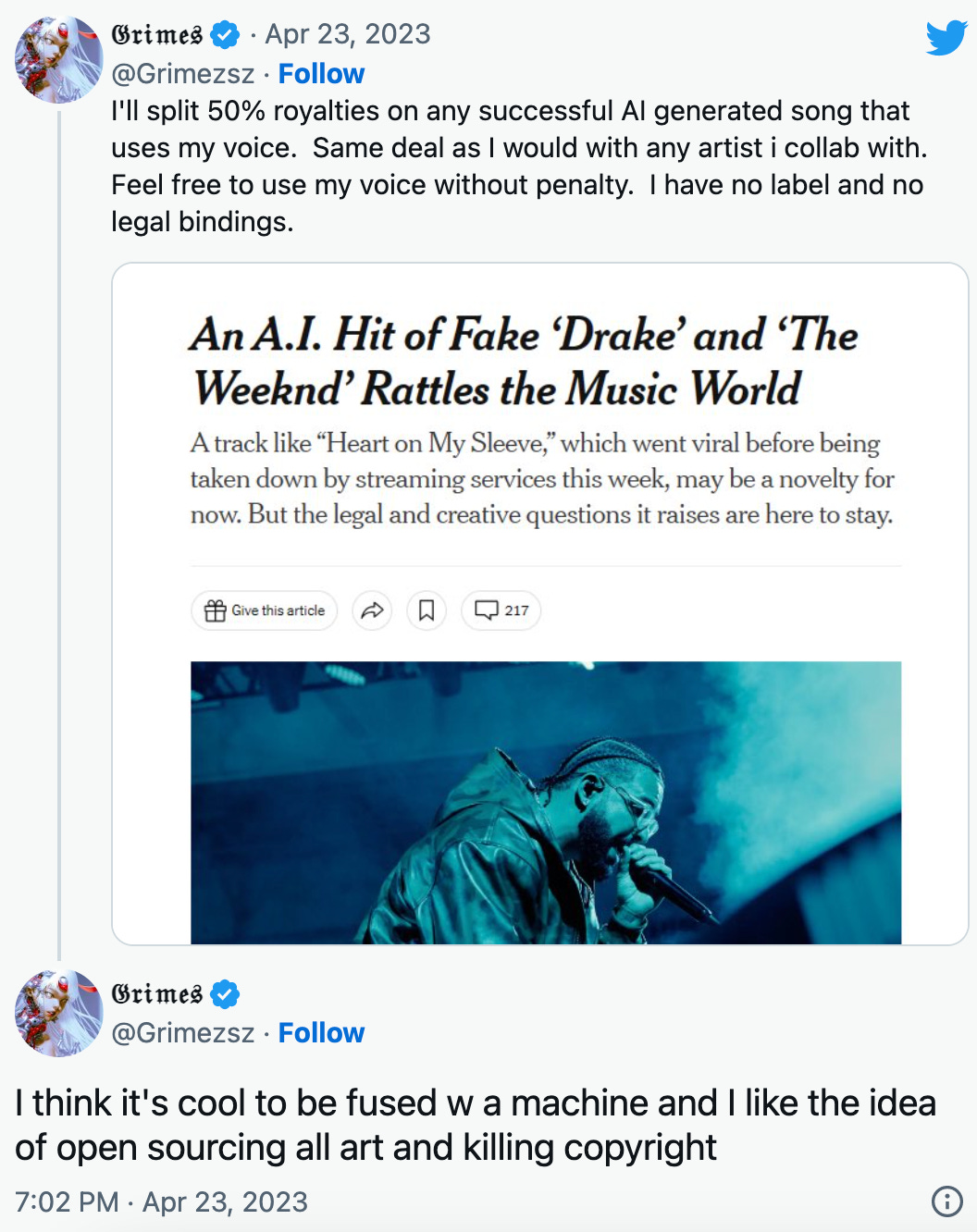

The question of liability is still outstanding, whether it should fall on the platform that enabled the creation, or the creator who prompted it. Grimes’s tweet implies that coordination or liability should be with the derivative creator or prompter, but precedent also exists for the former (i.e. platform).

One infamous platform example lies in Metallica v. Napster, in which the heavy metal band, a symbol for many artists, sued the peer-to-peer file sharing app for allowing Metallica songs to be circulated on its platform. Metallica alleged Napster was guilty of copyright infringement and racketeering—but did not hunt down the individuals who posted and shared Metallica’s songs on Napster. At the time, despite the ruling, many wondered whether the issue of piracy was realistically solvable.

Ultimately, a solution came. While imperfect, the elegance behind the rent-instead-of-buy model finally better enabled royalty payments. For example, Spotify pays artists per stream, then on the other side of the market charges ~$10 per subscriber per month. Finally, a platform identified a price point and level of convenience via instant streaming that was easier than illegally downloading each song. Some estimate that music streaming comprises over 80% of the U.S. music industry’s revenue today.

In the case of gen AI, I predict that plenty of cases will emerge that involve artists (“the originator”) suing both platforms and creators (creating “derivatives” in the artist’s NIL). Platforms will be forced to enable a compliant and safer model, such as:

Users pay a [higher] subscription fee to access NIL terms for prompts

Users pay the royalty fee per prompt involving NIL

Original artists are paid a NIL royalty fee on the backend by the platform, regardless of the user revenue model (similar to Spotify)

Platform does not allow the use of proper nouns in prompts (similar to Firefly)

Platform is required to have tech that scans for NIL or copyright (similar to YouTube)

Platform penalizes user for NIL or copyright when notified (similar to YouTube)

Currently, no one is paying for NIL in gen AI creations. To get ahead of the issue (or vice versa), different companies are taking different approaches. Amid the AI arms race, it remains an open question whether it’s better to quickly build and plow ahead to have the better and more popular product, or to mitigate liability risk from day one.

May the best LLM win.

The Supreme Court’s majority argued that "if an original work and secondary use share the same or highly similar purposes, and the secondary use is commercial, the first fair use factor is likely to weigh against fair use, absent some other justification for copying. ... The Court limits its analysis to the specific use alleged to be infringing in this case—AWF’s commercial licensing of Orange Prince to Condé Nast—and expresses no opinion as to the creation, display, or sale of the original Prince Series works. In the context of Condé Nast’s special edition magazine commemorating Prince, the purpose of the Orange Prince image is substantially the same as that of Goldsmith’s original photograph. Both are portraits of Prince used in magazines to illustrate stories about Prince. The use also is of a commercial nature. Taken together, these two elements counsel against fair use here. Although a use’s transformativeness may out-weigh its commercial character, in this case both point in the same direction."